Nutrition, Exercise, Stress Reduction, Holistic Wellness

Aging is inevitable.

Each and every one of us will continue to get older each and every day—until we die.

You might be thinking, “Gee, Jason, thanks for starting us off on such an upbeat note.”

Don’t worry, we’re headed toward an extremely upbeat note!

And we’re going to get there with pictures: three pictures from a scientific paper published in The Physician and Sportsmedicine.

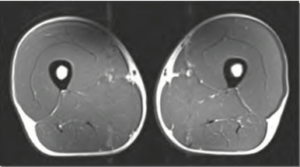

Here’s the first picture:

This is a magnetic-resonance-imaging scan of the upper legs of a 40-year-old man. Look closely, and you’ll see the femurs, the upper-leg bones, running through the middle. Outside the femurs, you’ll see the muscles of the upper leg. Around the edges, you’ll see body fat. (1)

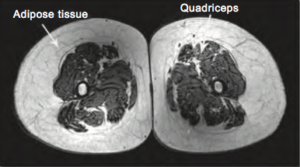

Here’s the second picture:

This is a scan of the upper legs of a 74-year-old man. Note the differences. Start with the femurs: They’re much smaller. Now, look at the muscles: They’re also much smaller. And, there’s much more body fat. I mean this in a descriptive, nonjudgmental way: These are decrepit legs. This is a decrepit person. These legs are wasting way. This person is wasting away.

Hang on, the upbeat note is coming!

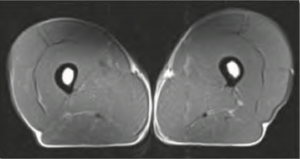

Here’s the third picture:

It looks a lot like the first one, right?

But it isn’t a scan of the upper legs of a 40-year-old man. It’s a scan of the upper legs of a 70-year-old man.

What the heck is going on here?

It’s simple. The first and third pictures are of consistent exercisers. The second picture is of a sedentary person.

To expound on this point, I’m going to hand the mic to the researchers who conducted this scientific study:

“The loss of lean muscle mass and the resulting subjective and objective weakness experienced with sedentary aging imposes significant but modifiable personal, societal, and economic burdens. As sports medicine clinicians, we must encourage people to become or remain active at all ages. This study, and those reviewed here, document the possibility to maintain muscle mass and strength across the ages via simple lifestyle changes.”

“This study contradicts the common observation that muscle mass and strength decline as a function of aging alone. Instead, these declines may signal the effect of chronic disuse rather than muscle aging. Evaluation of masters athletes removes disuse as a confounding variable in the study of lower-extremity function and loss of lean muscle mass. This maintenance of muscle mass and strength may decrease or eliminate the falls, functional decline, and loss of independence that are commonly seen in aging adults.”

“It is commonly believed that with aging comes an inevitable decline from vitality to frailty. This includes feeling weak and often the loss of independence. These declines may have more to do with lifestyle choices, including sedentary living and poor nutrition, than the absolute potential of musculoskeletal aging. In this study, we sought to eliminate the confounding variables of sedentary living and muscle disuse, and answer the question of what really happens to our muscles as we age if we are chronically active. This study and those discussed here show that we are capable of preserving both muscle mass and strength with lifelong physical activity.” (1)

There you have it:

Aging and deterioration are two entirely different things.

As such, you don’t have to deteriorate.

How’s that for an upbeat note?

Unfortunately, some people will read about this scientific study and use it as a license to exercise like a maniac.

That’s a very bad idea. Exercise is extremely beneficial but only to a point. Excessive exercise is as deadly as being sedentary. You heard that right.

To expound on this point, I’m going to hand the mic to the researchers who published an editorial in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings:

“From a population-wide perspective, physical inactivity is a much more prevalent public health problem than excessive exercise. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans call for 150 min/wk or more of moderate-intensity aerobic PA or 75 min/wk of vigorous-intensity aerobic PA. A recent survey of a half million adults in the United States reported that about 10 of every 20 people fail to obtain this suggested minimum weekly dose of PA. However, extrapolation of the data from the current Williams and Thompson study to the general population would suggest that approximately 1 of 20 people is overdoing exercise, potentially increasing the risk-to-benefit ratio. Individuals from either end of the exercise spectrum (sedentary people and overexercisers) would probably reap long-term health benefits by changing their PA levels to be in the moderate range.

Exercise is unparalleled for its ability to improve CV health, quality of life, and overall longevity. If the current mantra ‘exercise is medicine’ is embraced, PA might be best analogized as a drug, with indications and contraindications, as well as issues related to underdosing and overdosing. As with any powerful therapy, establishing the safe and effective dose range is fundamentally important—an insufficiently low dose may not bestow full benefits, whereas an overdose may produce dangerous adverse effects that outweigh its benefits. Fortunately, the exercise dose-response range that is safe and effective for improving CV health and longevity is broad. Although there is a concerted, research-based effort to reduce physical inactivity and prolonged periods of sitting, increasing data regarding the other end of the exercise continuum now suggest that it may be possible to have too much of a good thing.

On the basis of multiple studies, it might be prudent to limit chronic vigorous exercise to no more than about 60 min/d.”

“A weekly cumulative dose of vigorous exercise of not more than about 5 hours has been identified in several studies to be the safe upper range for long-term cardiovascular health and life expectancy.”

The take-home message:

Keep moving your body in ways you enjoy. But not too much.

“Of all the causes which conspire to render the life of a man short and miserable, none have greater influence than the want of proper exercise.”

—William Buchan

“Everything in excess is opposed to nature.”

—Hippocrates of Kos

Author’s Note: The scientific paper this article is based on doesn’t include a magnetic-resonance-imaging scan of a sedentary man in his 40s. I’ve shown you all of the scans included in the scientific paper.

(1) Chronic Exercise Preserves Lean Muscle Mass in Masters Athletes. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 2011, 10.3810/psm.2011.09.1933.

(2) Exercising for Health and Longevity vs Peak Performance: Different Regimens for Different Goals. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 2014, 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.07.007.

About Jason Gootman

Jason Gootman is a Mayo Clinic Certified Wellness Coach and National Board Certified Health and Wellness Coach as well as a certified nutritionist and certified exercise physiologist. Jason helps people reverse and prevent type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and other ailments with evidence-based approaches to nutrition, exercise, stress reduction, holistic wellness, and, most importantly, lasting behavior improvement and positive habit formation. As part of this work, Jason often helps people lose weight and keep it off, in part by helping them overcome the common challenges of yo-yo dieting and emotional eating. Jason helps people go from knowing what to do and having good intentions to consistently taking great care of themselves in ways that help them add years to their lives and life to their years.

Subscribe today, and get wellness tips delivered straight to your inbox.